Sommaire

- Une approche holistique de la maitrise de la contamination

- Part 2: Turning constraints into opportunities to accelerate Sterility Assurance performance

- Key Elements of a Successful Cleaning and Disinfection Program

- Améliorer la maîtrise de la contamination grâce à l’analyse de risque: un pilier de la stratégie CCS selon l’ICH Q9 et Q10

- The control of surfaces in cleanrooms: Questions & Answers

- Methods to Validate Disinfectants

- Clés du succès d’un projet de mise en place d’une solution de nettoyage GMP

- Nouvelle venue dans le monde de la désinfection ?

- Arrêté sècheresse : impacts & opportunités pour l'industrie pharma

Key Elements of a Successful Cleaning and Disinfection Program

Maintaining and improving cleanroom manufacturing operations are required to ensure quality products. In today’s world, there are many challenges facing cleanrooms and controlled environments and their support areas. Proper cleaning and sanitization of all cleanrooms and controlled environments are key to maintaining these facilities at the level for which they were designed..

1. Introduction

The science of surface contamination control requires overcoming the adhesive forces that hold matter to the surface; in order to remove surface particles, we must overcome one or all of the forces causing adhesion. Surfactant-based cleaning agents assist in reducing the surface tension and may be able to dissolve a portion of the soluble deposits on cleanroom surfaces. Cleanroom surface cleaning can be effectively accomplished by using a suitable cleaning solution. However, even the best cleaning procedures may prove unsatisfactory in the removal of all submicrometer particles.

Maintaining a clean surface is not as easy to achieve as air quality. HEPA filters and air handling systems can maintain the quality of the air and meet the ISO classifications. However, surface contamination—fibers, particles, organic materials, and process or product residue—will remain on surfaces until it is removed by wiping or mopping. A cleanroom thus may meet air particle counts, but the level of surface contamination may be unacceptable.

Today, as an industry, we face new challenges to surface cleaning and sanitization. These include:

- Workforce shortages to maintain these facilities

- The need for consistency of cleaning

- Management of cleaning and operations requiring strict attention to details and techniques

- Having adequate time for cleaning and other ancillary operations

- Rising costs of operations

- Cleaning solutions’ compatibility with products and processes

- Customer requirements

- Safety

- Changes in regulations

- Proper use of disinfectants and rinsing

- Sustainability

Each of these challenges can impact the ability to control particulate and microbial contamination.

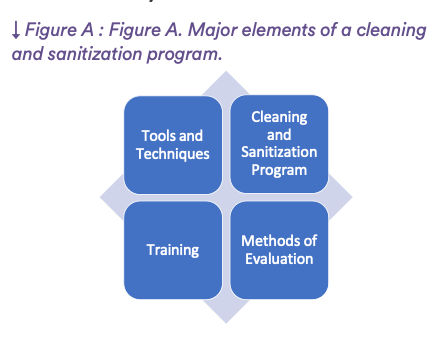

This paper will address four major elements (Figure A) of a cleaning and sanitization system.

2. Tools and Techniques

Sanitization is a system, and the validated solutions, contact times, proper techniques, and proper tools are all critical. The Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology (IEST) published Recommended Practice CC018.5 (IEST-RP-CC018.5), which is focused on operating and monitoring of cleanroom cleaning and sanitization.[1] Control of nonviable and viable particles on surfaces is required to complete the implementation of a surface contamination control program. Nonviable and viable particulates can destroy a product’s integrity and characteristics. Cleaning is the removal of visible and subvisible particulates and fibers on surfaces. Generally, this is done by vacuuming, if applicable, and wet cleaning.

Maintaining good manufacturing practices (GMP) requires that the building used in manufacturing be maintained in a clean and sanitary condition. Within regulations and other guidance documents are levels of cleanliness required for surfaces.[2]

Both viable and non-viable techniques are specified in IEST-RP-CC018.5 for the cleaning and sanitization of ceilings, walls, floors, horizontal surfaces, and equipment. These methods are the most effective because they impart the energy needed to remove contaminants. The “pull lift method” and the modified “figure 8” method are examples of good techniques. Conversely, spraying will not remove contamination from a surface and could transfer contamination to an adjacent surface. Any tool or equipment used for maintaining a cleanroom should be selected based on the classification of the facility and the types of surfaces to be cleaned.

3. Cleaning and Sanitization Program

3.1. Selection

Selection of the solutions used in any cleaning and sanitizing procedure should always meet the safety requirements of the facility. In addition, consideration should be given to the following:

a) Product compatibility – Does the chemical create any hazard to the product due to aerosolization or the critical surface cleaning residuals?

b) Process compatibility – Does the chemical impact the operation of the equipment, process, or electronics?

c) Cleanroom surface compatibility – Will the cleanroom finishes be affected by these chemicals (e.g., breakdown of the finish, rust, sealant damage, and so forth)?

d) Environmental compatibility – Where and how will the residual solutions be handled?

Cleaning agents and disinfectants should be selected and tested for the efficiency of cleaning on specific surfaces and be prepared at the proper dilution. Disinfectants must be applied with precision for contact time. Additionally, to achieve successful results, each solution must be replaced at a frequency based on room size, process type, or visible contamination in the solution.

3.2. Frequency

The process, product, equipment, level of activity, population density of the area, and cleanliness requirements determine the frequency of cleaning and disinfection. All surfaces may not have to be cleaned and sanitized with the same frequency. Surface testing and environmental monitoring will assist in this determination. Impact assessments and risk assessment tools can also provide an unbiased examination of frequency.

In some classifications, the control of microbial contamination will dictate daily or shift sanitization. This frequency is validated specific to the process, product, and regulations.

3.3. Surface Residuals

The image of clean is difficult to define as it varies from cleanroom to cleanroom depending on the classification, product, process, requirements, and visual acuity of the staff. In an industrial cleanroom that is not monitoring viable contamination on surfaces, the appearance of “clean” is defined as having no visible particles or fibers. Some surfaces will require no particles of a specific size range, e.g., 0 particles greater than 5 µm. Other pharmaceutical cleanrooms are concerned about surface molecular contamination specific to chemical or process residuals, and cleanroom staff test these surfaces to ISO 14644 Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments—Part 10: Assessment of surface cleanliness for chemical contamination.[3] In these cleanrooms, the frequency, tools, and cleaning agents are selected based on the required quality results supporting the process, product, and cleanroom classification.

In cleanroom facilities where viable contamination on surfaces is of primary concern, the disinfectant residuals can be a concern critical to achieving the monitoring limits. Disinfectant residue buildup could leave particles on the surface and potentially create a product concern. This residual, in many cases, is a result of improper training in techniques of mopping and wiping. Removal of this buildup can be achieved by the application of a rinse or a cleaning agent with a specific frequency. The rinsing or cleaning application can be immediately followed by a disinfectant application to ensure that the surfaces will maintain the microbial control as validated.[4]

3.4. Disinfectant Rotation

In cleanrooms where microbial contamination is a concern, the topic of disinfectant rotation has been discussed and researched for many years. However, there is no evidence whatsoever that resistance could or would occur. It is thought that initially this concept arose in the pharmaceutical cleanroom industry as a misapplication of the true phenomenon of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. The development of microbial resistance to antibiotics is a demonstrated fact, and relies upon two conditions:

a) Successful propagation of microbial species, and

b) Random occurrence of gene-specific mutations that convey resistance to the mechanism(s) of antibiotics.

Neither of these two conditions exist in the cleanroom environment. Given the environmental conditions of cleanrooms (i.e., low humidity, low temperature, lack of available organic material), the first condition for development of microbial resistance does not occur, namely that bacteria are not successfully replicating in these environments. The second condition, that a random gene mutation that confers resistance to the mechanism of action of antibiotics arises, also cannot occur in the setting of liquid chemical disinfectants. The mechanism of action of antibiotics is indeed gene specific and thus susceptible to gene-specific random mutations. The mechanism of action of chemical disinfectants, however, is not relegated to a single gene or protein pathway; rather, disinfectants work via chemical obliteration of bacterial cell wall functionality.

The concept of preexisting microbial species that are unaffected by certain chemical disinfectants is indeed true enough: many broad-spectrum disinfectants have limited or no biocidal effectiveness versus mold species, and bacterial endospores pose a special challenge as they have innate resistance to many chemical entities and to extreme environmental conditions (e.g., low or high temperatures, radiation, desiccation, and so forth). This, however, is precisely why the judicious use of a sporicidal agent, at frequencies determined by actual environmental monitoring data and the frequency of occurrence of fungal and bacterial spores, is the most scientifically sound approach to “rotation.” Amongst companies and regulatory bodies alike, there is growing acceptance in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere for the concept of a single disinfectant rotated with a sporicidal agent.[2,5] Certainly, in the United States, the FDA is amenable to alternative approaches, even those that diverge from the FDA’s own guidance documents and the US Pharmacopoeia (USP), given there is a scientifically supported, written rationale that addresses the chosen approach. It is contingent on the individual company to clearly state their reasons for

the selection and the “rotation” of a broad-spectrum disinfectant and a sporicidal agent, but with few exceptions, there is no longer a regulatory expectation that the “rotation” must include two differing disinfectants plus a sporicidal agent, as the concept of developed/selected microbial resistance to liquid chemical disinfectants has been thoroughly discredited.

The theory of disinfectant rotation was based on the premise that microorganisms (bacteria) may mutate and become resistant to disinfectants. This theory of resistance was debunked in 2000 with USP <1072>[5] and again in 2005 with an article and book chapter by Dr. Scott Sutton.[6,7] PDA Technical Report No. 70 states the following regarding resistance: “The antimicrobial agents typically employed in cleanrooms continue to be effective because they have numerous effects on a number of aspects of cellular physiology. That means multiple random mutations would be required in a short period of time (e.g., 5 minutes) with exposure to low numbers of cells typically found in a cleanroom to overcome their detrimental effects. As such, resistance of a cell to agents used in a disinfection process would be highly unlikely given the environmental conditions and low cell number.”[2] Additionally, there has not been a documented case of microorganisms becoming resistant to a disinfectant in a pharma/biopharma cleanroom operation. What is seen in cleanrooms is the presence of fungal and bacterial spores; a strong oxidative chemistry (e.g., hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid, sodium hypochlorite) is required to kill and inactivate these spores in cleanrooms. The current industry stance is to have an effective broad-spectrum disinfectant to address vegetative bacteria and some easier-to-kill fungal spores and rotate in a sporicidal agent on a periodic cadence based on environmental trending data and the presence of fungal and bacterial spores.[2,5,8] There are some cleanroom operations that choose to rotate two disinfectants and a sporicide, which is not necessary but still acceptable with industry regulators. A recent industry article by Crystal Booth says it best with her quote, “Clearly explain your cleaning and disinfection program, and then demonstrate through data how your program is effective in microbial contamination control.”[9]

The disinfectant selected must be prepared at the proper dilution rate and applied with precision for contact time; further, the use of dilution needs to be changed out on a routine frequency to allow for successful results.

4. Training

The documents referenced provide the appropriate tools, solutions, and methods for surface contamination control. The practical application of these cannot be acquired and absorbed simply by reading documents. These skills must be taught and practiced. The basic concept of “clean” is difficult to comprehend, as removal of non visible particles is not relatable to daily life.

Classroom training, hands-on training, followup discussions, and regular auditing are all required to achieve the required results.

5. Methods of Evaluation

Any product or process could become contaminated by direct or indirect contact with a contaminated surface, or the operator touching a surface could contaminate a process as personnel in cleanrooms are the number one source of contamination. Surface sampling will determine the quality of the cleaning and sanitization procedures. Sampling performed immediately after any procedures will only indicate the effectiveness of that clean and not the effectiveness of those procedures over time. Cleaning should be tested to determine the frequency.

There are numerous methods for determining the cleanliness of a surface. This paper will only address some of the common methods as they relate to cleanroom and controlled environment surfaces.

- Wipe inspection

- Light inspection

- Contact plate method

- Swab method

Visual inspection provides an overall assessment of the condition of the cleanroom or controlled environment. A wipe inspection is a very simple method for detecting particle contamination on surfaces. Simply wipe the surface and examine the wipe for particles, residue, and so forth.

Ultraviolet light inspection causes certain organic materials to fluoresce. However, not all fluorescent material is contamination. The wavelength must be 365 nm. (Safety requirements must be followed when using this type of inspection.) The light levels in the cleanroom or in controlled environments should be reduced to perform this inspection. Under these conditions, fluorescent particles will appear larger on surfaces. This is a qualitative method for determining the surface cleanliness but could be quantitative with the addition of analytical collection tools.

The two methods of determining viable surface contamination are the contact plate and swab methods. The contact plate method is used for detecting microorganisms that may be present on flat surfaces. The swab method is used for detecting microorganisms on other-than-flat surfaces, difficult to reach areas, and critical equipment surfaces. Both methods are defined in the USP.

The environmental monitoring limits are determined by product quality, process, customer requirements, and regulations. These limits are generally determined prior to the design of a facility and are tested prior to startup. However, as processes change, as equipment is added or changed, and as personnel are added, the impact to these limits must be assessed. This impact could necessitate a change to the frequency of cleaning and sanitization.

Jim POLARINE

Anne Marie DIXON-HEATHMAN